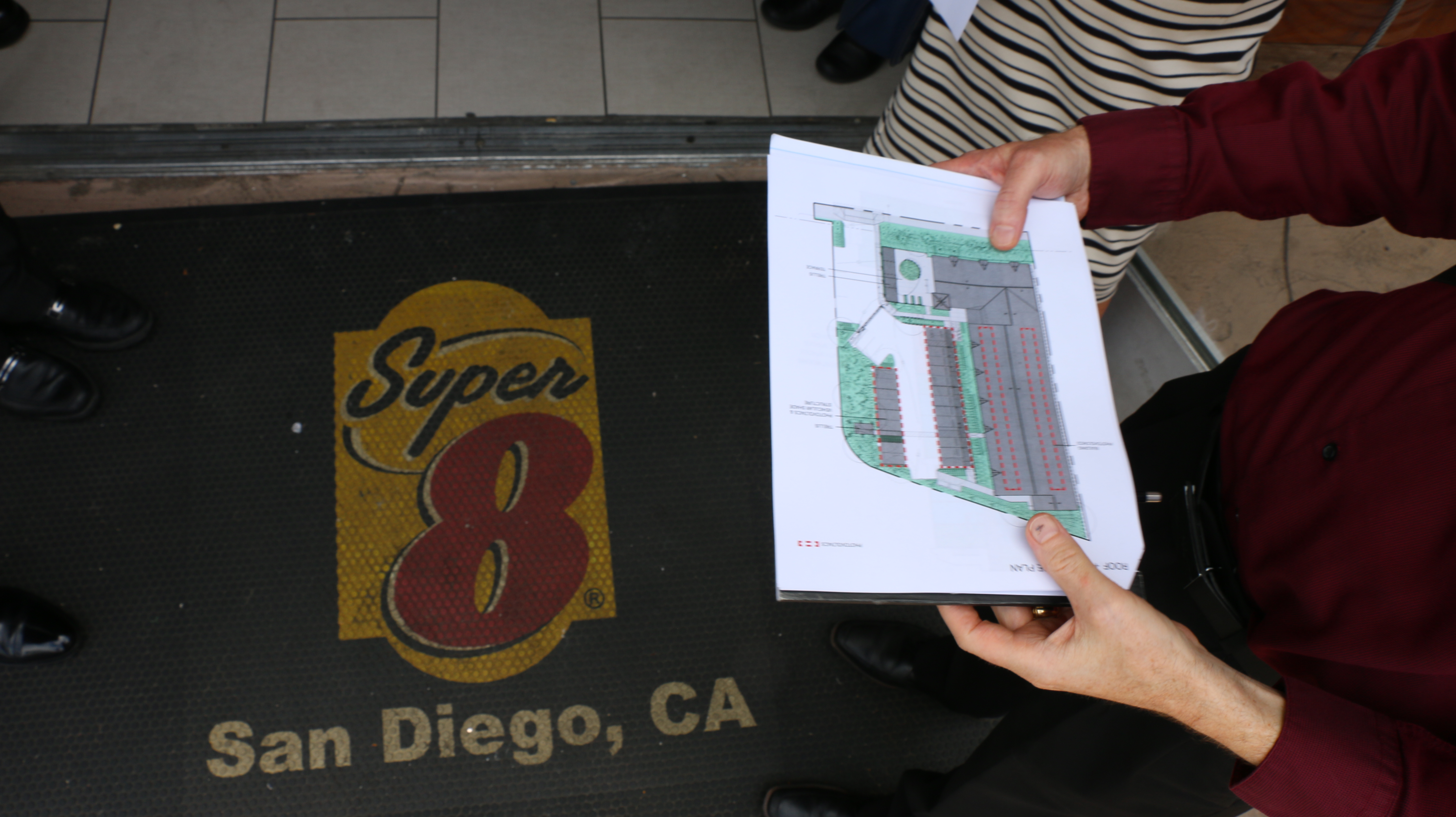

The former Super 8 motel is being transformed into the Palm Avenue Transitional Housing project.

Collaboration is Key to San Diego Prop 47 Program

SAN DIEGO – A renovated Super 8 motel once favored by drug users and sex trade workers is central to a local effort to help precisely those kinds of justice-involved individuals get off the streets, stabilized and into supportive treatment.

In a region known for high real estate prices, safe transitional housing was one of the biggest challenges facing the city-county coalition receiving funding from the Proposition 47 grant administered by the BSCC. Buying the motel seemed like a way for City of San Diego to solve two of the city’s pressing problems: removing a nuisance while creating a supportive environment for recovery.

|

The remodeled 70-bed motel, with treatment programs, a health clinic, gym and other services, is scheduled to open in February 2019 for those who agree to join the City Attorney’s San Diego Misdemeanants At-Risk Track (S.M.A.R.T.) program, one of two projects funded with help from a $6 million Proposition 47 grant and $6.5 million in leveraged funds.

The County of San Diego is collaborating with the City Attorney’s Office to oversee expansion of the SMART program and the implementation of two new county programs for Community-Based Services and Recidivism Reduction (CoSRR).

The StrengTHS and Recovery for Life programs serve misdemeanants in the central and northern regions of the county. Both programs already are at work to reduce justice-system involvement of people impacted by Prop 47 crimes, and the future opening of the remodeled motel will serve to enhance available housing options for current and future S.M.A.R.T. program participants.

The programs serve adults who have been cited, arrested, booked into jail or charged or convicted of a Prop 47-eligible offense such as drug use and possession, and petty theft. Some suffer from co-occurring mental health issues. Most have experienced homelessness.

|

Referrals are made by public defenders directly to a StrengTHS and Recovery for Life court liaisons and by outreach workers at the jails and courts, who screen eligible clients and schedule their first substance-use disorder treatment appointments. Through S.M.A.R.T., referrals are made through diversion by police officers, and by city attorneys and public defenders at the courts, or by outreach workers in the community. All who qualify for S.M.A.R.T. are offered chances to participate at each step of the criminal justice process and can avoid a formal charge altogether by accepting help.

The County program has contracted for therapeutic services with the community-based Episcopal Community Services (StrengTHS) and North County Lifeline (Recovery for Life). The S.M.A.R.T. program works with Family Health Services of San Diego for community-based help such as relapse prevention, housing, job skills and vocational services. The county passes 89 percent of its grant award directly to the community-based providers.

“The County, City and the community-based providers show what is possible when people work collaboratively to improve their communities,” said Ricardo Goodridge, the BSCC Field Representative who oversees the Prop 47 grant.

The grant requires recipients to deliver evidence-based programs and practices. For instance, the Recovery for Life provider has been trained by the University of Cincinnati to ensure programs are delivered with fidelity.

The goal is that with enough support, these vulnerable low-level offenders will stop cycling back to jail through the criminal justice system. Therapy delivered by empathetic counselors is working for many.

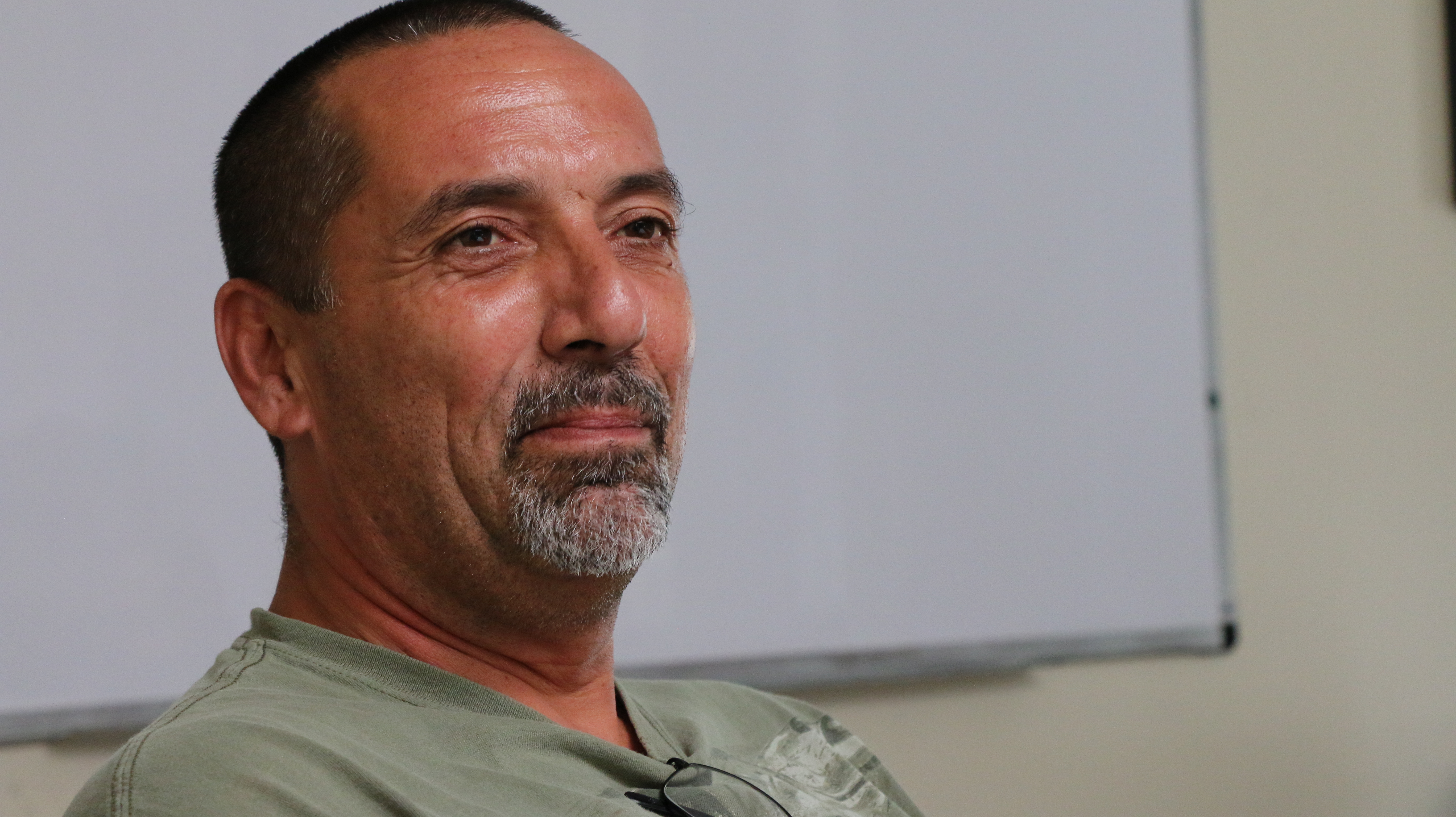

“These guys gave me tools. They taught me how to recognize anxiety and taught me how to ease it,” said Mitchell, who is in the S.M.A.R.T. program and receives services at the Family Health Services of San Diego. “I was a revolving door. I said give me a chance and I’ll show you what I can be.”

Their work has shown that many participants have self-medicated with drugs and alcohol for years, especially those whose parents didn’t recognize mental illness in their offspring and punished anxious behavior as being “bad.”

Program administrator Dorothy Thrush, who is Chief Operating Officer of the county’s Public Safety Group, says the goal is to identify and address the issues that have caused participants to become addicted, help them get physically and mentally healthy, and give them support to learn the skills needed to lead better lives.

“That’s why we are focusing on post-treatment support,” said Thrush.

San Diego County filed the highest number of Prop. 47 petitions for relief in the state, with 20,500 sentence reductions granted by 2016. While felony arrests decreased after Prop 47, the number misdemeanor arrests increased from 59,527 to 66,978 in 2015.

The San Diego County Prop 47 grant program was designed to engage 200 people a year, but after years on the streets change comes slowly for this population. Six months into the grant only a fraction of those eligible were willing to commit to change.

“I had to get sick and tired of my life,” said a participant in the Episcopal Services support services named Ricardo. “(Outreach worker Gary) approached me at the jail and said ‘I know you’re tired of getting high. This is the program for you.’ I didn’t like the drugs; I didn’t like the people. Now I’ve been here three months and it’s my safe-haven.”

Outreach workers trained in motivational interviewing know they must build relationships first and aren’t deterred by rejection. They have reason to believe that persistence pays off.

“For them to come see me in jail after I cussed the lady out…” Mitchell’s voice trails off as he recalls his initial reaction to an offer of help. “Well, she had the kindness to come back to jail and say, ‘let’s try it again.’”

|

LaKiesha Wilks, Program Coordinator for Substance Use Disorder Services at Family Health Centers of San Diego, understands the physiology behind the outbursts so she is undeterred by rejection.

“That anger speaks to the addiction, not the individual,” she says. “So no, it doesn’t bother me. We will keep offering help as long as it takes.”

People who agree to participate are given a “warm handoff” to treatment and temporary housing.

“We make five to 15 offers a week,” said Angie Law, who serves as the Chief Deputy City Attorney in charge of the Neighborhood Justice and Collaborative Courts Unit. “If they decline at initial citation but decide later in the process to accept S.M.A.R.T., all it takes is a phone call to their public defender.”

With integrated care, counselors address the underlying substance-use and mental health needs contributing to criminal behavior. Transitional housing and job training are part of both programs and contribute to a participant’s sense of security and well-being.

|

It is working for David, who volunteered at Kitchens for Good and eventually became a culinary apprentice. He now has a job as a cook, and he still volunteers at Kitchens for Good preparing meals for low-income families. He has learned how to love himself, he said, which brought him out of hopelessness.

“I feel purposeful again,” he said. “That is everything. Without that things might have turned out way different for me.”

The philosophy of the programs is “harm reduction,” which does not mean zero tolerance. Mitchell knows first-hand. When he relapsed, he was given another chance to get out of jail and off the streets.

“I’ve been in other programs, but this is the only one that really cared. I signed up for this one and relapsed and went to jail for 14 days. They came to talk to me and said ‘Do you want to try it again?’ That took my heart.”